The University Archives turns 70 on 3 May this year. To celebrate this milestone, check the blog at the end of each week for the week’s special stories from our collections.

25 March 2024

Cabinet Pudding and an Evening Lecture

On 24 March 1884, the first Evening Lecture was held and attended by 31 students, one of whom was female. In a University of Sydney News article celebrating the centenary of the Evening Lectures, Vice-Chancellor John Manning Ward wrote, “Professor Badham, who had been among the foremost advocates of evening classes, died too soon to be present when his distinguished colleague, Dr John Smith, the Professor of Chemistry and Experimental Physics, welcomed the first 31 students. Before delivering his lecture, Smith paid a warm tribute to Badham’s work for evening classes”. Ward also recognised that the admittance of a female student would have “delighted” Professor Badham, “…for he had often spoken in favour of admitting women to University courses and degrees”.

In 1888, two years after the first lecture, a committee was appointed to report on the system of Evening Lectures. The report included a letter from Professor Rudolph Max, Professor of German, to the Registrar [HE Barff], which noted that, “In the last year’s French examination, the evening students did the same papers as the morning students and a far greater percentage of the former passed. The reason of this I find in the circumstance that the evening students are older and more in earnest about their work, many of them being Public School Teachers. A great number of ladies have assured me that they willingly would join my Evening Lectures if the University were not so far off, and if the avenues leading up to it were not so dark”. The sentiments of Professor Max were seconded by Professor of Mathematics, Arthur Newham, who wrote, “It is hard work for any one who is employed all day to attend classes at night, and prepare the necessary work for the lectures, and the position of the University makes it harder. There are several of my pupils who do not reach home in the evenings till nearly 12 o’clock”. The report, recognising the success of the Evening Lectures, recommended to Senate that they, “…should be delivered in a more central place than the University” to allow more students to attend.

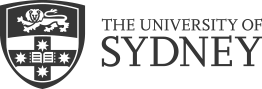

In April 1900, the Sydney University Evening Students Association was founded, “…with the object of promoting social relations among Evening Students, past and present”. On 10 December 1921, the Annual Dinner of the Association was held at the Burlington Café. In the 1922 edition of Hermes, Honorary Secretary of the Association, Norman W Drummond called the night “…an unqualified success”, remarking, “While giving an opportunity for a re-union of past and present evening students, it also provided an opportunity for a stirring utterance by the Chancellor, Sir William Portus Cullen, K.C.M.G., who appealed in irresistible tones for the support of every member of the University in the conduct and development of University affairs”. Throughout the evening, monologues and musical items performed by “Messrs. Montgomerie Stuart, WH Matheson, G Morrow, L McCarthy, and RV Cleary (accompanist)” kept the diners entertained.

Evening Students Association Annual Dinner Menu, 1921 (10/12/1921), [REF-00072499]. University of Sydney Archives, accessed 25/03/2024, https://archives-search.sydney.edu.au/nodes/view/122072.

26 March 2024

Practical Rather Than Ornamental

In 1923, University Architect Professor Leslie Wilkinson completed the designs for an arch that would stretch across Science Road, connecting the Quadrangle to the Macleay Building. His design included, “…a large central pointed arch for vehicular traffic and…smaller Gothic-arched openings at either side for pedestrians”. It was intended that the single room above the bridge would be used as professorial offices.

Thirty years later, at the 10 August 1953 Senate meeting, a, “…lengthy discussion took place during which the many aspects of the Appeal objectives were considered”. The Appeal in reference was the Centenary Appeal, which sought to raise funds for the celebration of the University’s Centenary. At this meeting, Senate confirmed that a portion of the Appeal, “…be allocated for the setting-up of a specific form of war memorial for World War II, which would be practical rather than ornamental”. Senate appointed Professor Wilkinson and Professor Henry Ingram Ashworth as joint architects for the project.

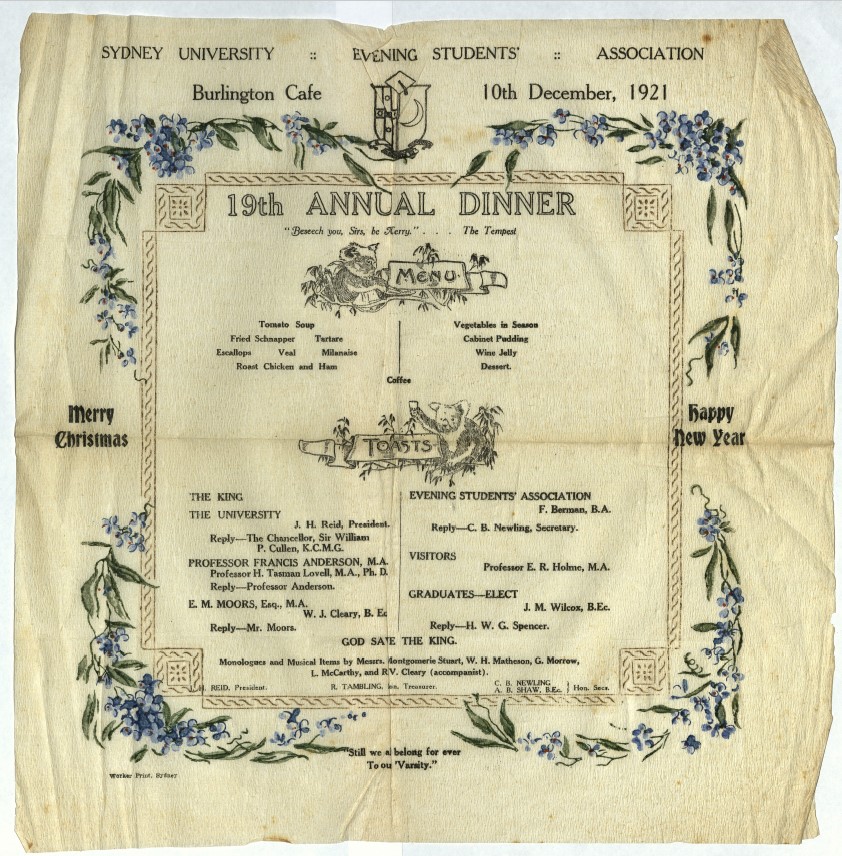

Based on Professor Wilkinson’s original design, Professors Wilkinson and Ashworth presented their design for the Memorial Great Gate and Fine Arts Gallery. Their design involved the construction of a, “…Great Gate across the head of Science Road, where the incomplete abutments have stood for many years…Its completion would unify the main Gothic front, provide a fitting entrance to what would become an inner precinct, and make a natural division between the stone faced buildings forming the gothic east and the stuccoed group of buildings to the west”. The original plan to use the enclosed room above the Great Gate as professorial offices was amended to instead house a Fine Arts Gallery, addressing the pressing need for an exhibition and gallery space on campus. Despite the Chancellor, “…later question[ing] the desirability of going ahead with a building which would permanently reduce the width of the roadway to ten feet”, the design was approved by Senate.

As construction neared completion, a committee was formed to finalise the inscriptions that would adorn the exterior of the Memorial Arch. The committee recommended the years 1939 and 1945 be inscribed into the stone and also, “…considered designs which were available for inspection representing the Army, Navy, Air Force and Women’s Services”. In a letter to Professor Wilkinson, Professor Ashworth described the designs as four shields, where the Navy was represented with an Anchor and Crown, the Army with a Rising Sun and Crown, the Air Force with an Eagle and Crown, and the Women’s Services with a Lighted Lamp (representative of the Nightingale Lamp) and Crown.

Construction of War Memorial Arch (1950s), [REF-00077095]. University of Sydney Archives, accessed 26/03/2024, https://archives-search.sydney.edu.au/nodes/view/127281.

27 March 2024

The Energy Field

On 6 September 1983, the University of Sydney News reported that the University and Rheem Australia Limited had signed a solar energy development licensing agreement which meant that, “In years to come, buyers of Rheem solar hot water systems may be able to opt for sets of glass tubes on their roofs, rather than the all-metal ‘flat plate’ collectors are used to”. This momentous collaboration for the School of Physics was the culmination of years of effort, money, research and time.

The School of Physics begins its foray into solar energy research around 1975, which Professor Harry Messel discusses in a 2009 interview with Dame Leonie Kramer, “I felt that I should do something which I felt was of tremendous importance to Australia and that was in the energy field. I decided to start phasing out from the environmental field in Northern Australia and from the radio tracking devices…I then established a solar energy laboratory in the School of Physics. The University of Sydney was very supportive of this technology and this latest development in science and provided a grant for three years, that was a special developmental grant…by 1976, we had made an important breakthrough in the technology by developing special selective services for absorbing the sun’s rays. And the University then was able to take a patent on this…The University had provided the original funds but I knew it was only for three years”. As Professor Messel feared, the University’s offer of funds was not extended. However, the work of the School of Physics had Saudi Arabia interested and on 22 November 1977, the University signed an agreement with Saudi Solar Energy, who provided $5 million to help the School continue its work on solar energy research and development.

This grant, backed by the Royal Highness Prince Nawaf Ibn Abdul Aziz of Saudi Arabia, coincided with Australian Government funding, as Professor Messel recalls, “At that very moment the secretary comes into the office and says, ‘Professor, there’s an urgent call for you from Mr. Wran [Premier Neville Wran], will you come out and take it?’ So I came out and said ‘Yes, sir Premier?’. He says, ‘What are you doing?’, I said I’m in Canberra begging for money. He says, ‘Why?’ I said, ‘Because my solar energy group is going to be closed down I got a letter from the University, it’s going to be closed down’. He says it’s not going to be closed down. I say, ‘Yes, it is Premier.’ He says ‘I’m telling you it’s not going to be closed down… ‘Now what do you need?’ So I told him the whole story of what had happened. He says, ‘How much do you need?’ I say, ‘Two million dollars, Premier’. He heard the story. He says, ‘Jerry, you see that the University gets the two million dollars.’ ‘Yes, Premier, thank you.’…A couple of weeks later, you know, we got the two million dollars from the Premier”.

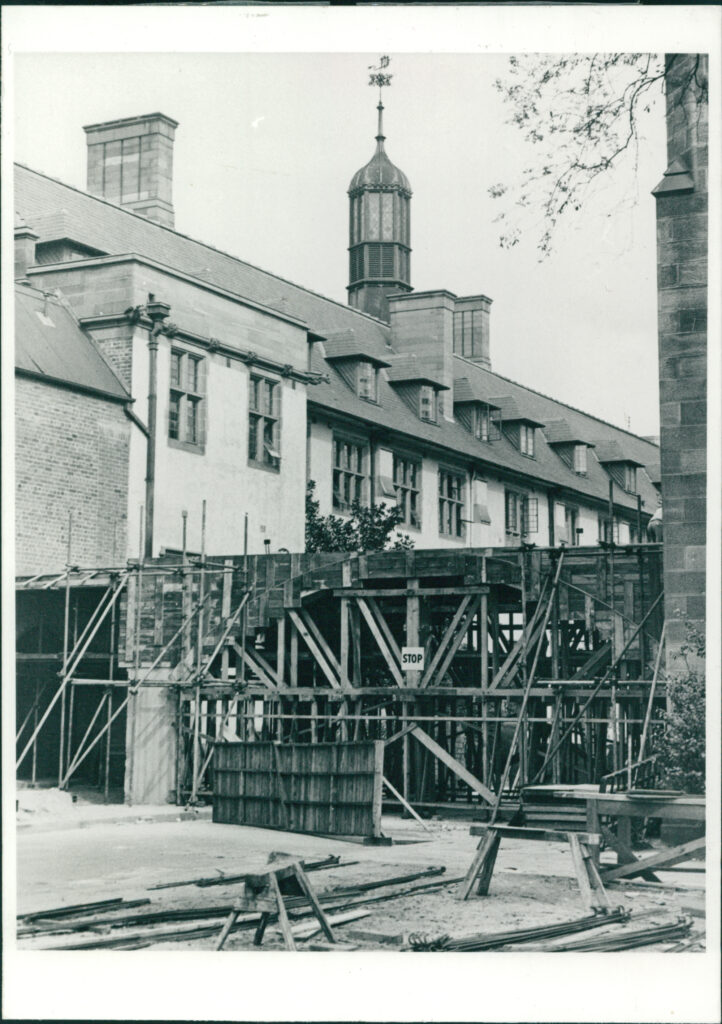

This image, taken in 1977, was an occasion when “‘…Professor Messel cooked some bacon and eggs for us while we were here…Some of the more daring members of the media team tried them, but the more cautious politicians only pretended to have them.'”. Premier Wran’s excuse was that the bacon and eggs contained too much cholesterol, however, the coffee, made with water boiled using solar energy, provided to him in 1983 was acceptable posed no such health problem.

Premier Mr Wran Pretends to Eat Eggs and Bacon Cooked in Solar-Heated Oil with Professor Messel (April 1977), [REF-00013404]. University of Sydney Archives, accessed 27/03/2024, https://archives-search.sydney.edu.au/nodes/view/33285.

28 March 2024

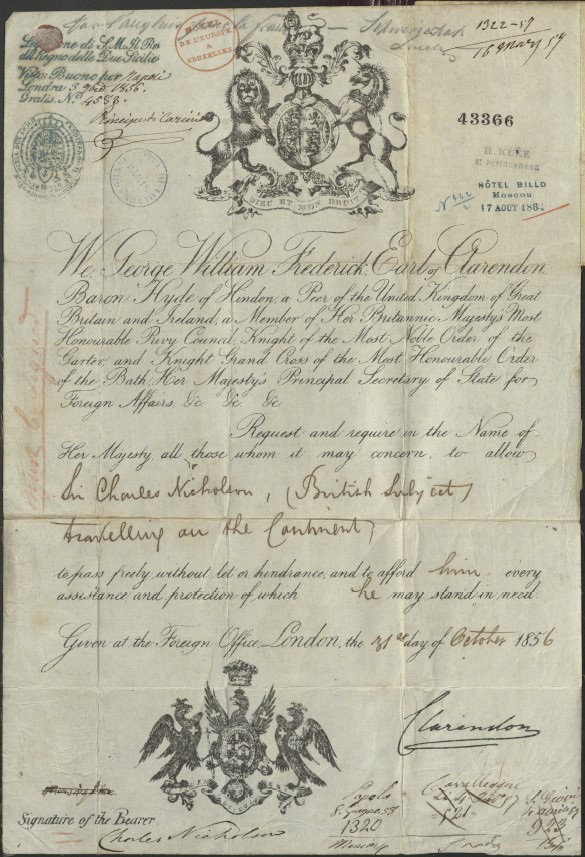

You May Pass Freely

Just two years after being elected Chancellor of the University, Sir Charles Nicholson departed Australia for a two-year trip to England and Europe. This passport, issued to him before his departure, allowed him to, “…pass freely without let or hindrance and to afford him every assistance and protection of which he may stand in need”.

Despite being on the other side of the world, in his role as Chancellor, Nicholson continued to advocate for the University. In 1857, he secured a Royal Charter for the University from Her Majesty Queen Victoria and received a grant of arms from the College of Heralds. He also spent time in England collecting donations for stained glass windows in the Great Hall. In a letter sent from London in 1856, Nicholson wrote to Thomas Barker, “To give proper effect and harmony to the design of the Great Hall and to render it complete as a monument of the age – it is desirable that the tracery of all the windows – 14 in number – should be filled with stained glass – presenting the best specimens procurable of that beautiful art – in which of late so much improvement has been made. As however these cannot be provided for from the public endowments it is hoped that a number of Colonists may be disposed, each to furnish a separate window…Should you think fit to comply with this invitation and forward the amount of your contribution to me, I will take care that it is faithfull and judiciously applied”. Barker contributed £100 for a side window in the Great Hall.

Included in his passport are visas to a number of European countries, where Nicolson collected antiquities, which ultimately formed the basis of the Nicholson Collection and later Museum.

Passport of Charles Nicholson (1856 to 1858), [REF-00089776]. University of Sydney Archives, accessed 28/03/2024, https://archives-search.sydney.edu.au/nodes/view/142643.

Explore the blog for other posts from the University of Sydney Archives and follow us on Instagram.