The University Archives turns 70 this week on 3 May! To celebrate this milestone, we have published 70 special stories from our collections. This is our final 70 Years, 70 Stories week and we hope you have enjoyed the series. Stay tuned for our regular Favourite Four, Flashback Friday, and Then and Now posts from next week!

29 April 2024

Swallow 698 Feet Hen

In a letter to the Chancellor, dated 22 February 1897, Professor of Geology, Professor Tannatt William Edgeworth (TWE) David requested a leave of absence to undertake a scientific expedition to Funafuti, a coral atoll located in Tuvalu (known at the time as the Gilbert and Ellise Islands). Professor David wrote, “For some fifty years past it has been the earnest wish of men of Science, and notably of Darwin, to gain definite knowledge as to the true mode of origin of coral reefs by means of putting down a bore in a typical coral atoll, and thus securing cores of the coral rock, from the surface down to depths of 500 or 600 feet. A careful examination of these cores in scientific laboratories would subsequently reveal the bore structure and mode of origin of atolls”. Professor David’s voyage followed a failed expedition organised by the Royal Society of London and led by the British geologist, William Johnston Sollas the year before.

The small expedition party, comprised of Professor David, his wife Cora, and a handful of drill men and foremen, arrived in Funafuti on 19 June 1897. The expedition was plagued with problems from the very first day of drilling with the initial rock on the reef platform being, “…so tough that the drill was running for several hours without boring more than an inch or so”. After breaking through the tough layer of rock, the party was then faced with two serious mechanical issues – a dangerous failed attempt to set up a boring drill in the deepest part of the lagoon, and a broken drill part that took multiple days to recover from deep inside the borehole, which nearly forced the party to abandon their site to begin drilling in a new location.

In a diary penned following his return to Sydney, Professor David recalled, “The outlook was none too hopeful. It was nearly a month since we landed: we had bored only 118 feet, had had two serious accidents, and were reduced now to our last set of lining pipes; we knew if anything happened to them like that which had happened to the 5 inch pipes the boring would be a failure. The foreman of the drill, Hall, was becoming seriously ill, and we feared his leg would mortify, while one of the foreman and one of the drill men were also suffering, though less severely, from ulcerated legs”. The expedition was saved, however, when a, “…deus ex machina arrived on July 18th in the person of Dr Corney in the Government Steamer ‘Clyde’ from Fiji”. With him, Dr Corney brought mail from Sydney, fruit, “…cash forwarded by Mr Pittman from Sydney”, and most importantly, “…a good supply of medicines”.

With the party’s spirits improved, the drilling continued, albeit with further delays when various parts of the boring drill required fixing. “At last, however, so serious a break occurred in the crown gearing wheel that the artificer considered that it was impossible to repair it without very considerable delay. We were therefore much surprised on our return to the drill camp a few hours later to find that the drill was again in full work. The explanation was a [sic – as] follows; One of the natives named Tili on seeing the artificer commencing to repair the broken wheel exclaimed that he had got one just like that himself, and presently produced a wheel the facsimile of the broken one, with the exception that it was not broken but only somewhat worn, which he had just dug up from the roots of one of his cocoanut palms. He had placed it there so that the iron might act as a fertiliser for his palm. The explanation also as to the mystery as to how he came to be possessed of the wheel was easily given. On the occasion of Professor Sollas’ expedition in 1896, amongst the very few articles left behind was a bevel gearing wheel the counterpart of the one we had broken…This piece of good fortune enabled us to continue the boring without serious delay; as while one gearing wheel was in use, the duplicate not in use was being repaired”.

On 5 September 1897, the London Missionary Society’s steam yacht ‘John Williams’ arrived in Funafuti to transport Professor David and his party back to Sydney so Professor David could resume his University duties. Despite the numerous, and often serious, issues the party faced, the expedition was ultimately a success as, “The cores recovered supported Darwin’s theory that the coral atolls had been built upon a sinking platform”. Professor David used these cablegram codes during his time in Funafuti to send word of the expedition’s findings. Written in pencil below the codes is his cablegram, reading, “swallow 698 feet hen. boilers failed. partridge returned Sydney finis. (End) David”.

Funafuti Expedition Field Notes (1897 to 20/12/1900), [REF-00090004]. University of Sydney Archives, accessed 29/04/2024, https://archives-search.sydney.edu.au/nodes/view/142894.

30 April 2024

A Lot of Back Chat

The Air Raid Precautions (ARP) Committee was established by the University to, “…ensure that the University…shall be able to carry on its normal activities for as long as possible with the least amount of dislocation” during World War II. But despite what must have been trying times, the Committee attempted to arrange a social gathering, albeit with disappointing consequences.

On 30 October 1942, Nightwatchman, G Sharp wrote to the Vice-Chancellor, “I have to report that car LX809 crashed into and dislodged one of the large stones of the retaining wall in front of the Main Building…was hanging over with front wheels on the lower lawn. This happened at 2am after the A.R.P. Dance. It took six men to lift it up by the front and push it back. I then got the Driver to write his name and address which is attached to this report. Several of the people gave me a lot of back chat both male and female”. The University took swift action, writing on the same day, to the Department of Road Transport and Tramways, requesting the name and address of the owner of the car, “…so that the University authorities may take suitable action. The occupants of the car were not at all helpful to the Night Watchman who appeared on the scene some time after the collision occurred”.

This was followed by an internal memorandum updating the Vice-Chancellor that, “It appears that a dance was held in the Union Hall last night and that the people who attended it were A.R.P. persons…The people in the car which was involved in the accident…were evidently not University people. I find that a coping stone of some considerable weight was dislodged from its site and was thrown by the impact of the car on to the lower lawn. Another coping stone has been slightly shifted…asked…to have the stones reset to their former positions. The stone are of great weight and the replacement of the one dislodged will need shear legs. The site…is almost opposite the Great Hall door…It would appear that social functions similar to the one held last night should not be repeated”. A handwritten note on this memorandum reads, “any compensation?”.

Air Raid Precautions – Emergency Services in University Grounds (25/08/1939 to 30/10/1942), [REF-00043679]. University of Sydney Archives, accessed 30/04/2024, https://archives-search.sydney.edu.au/nodes/view/82054.

1 May 2024

History is Full of Them: Flying Saucers or Optical Illusions?

On 5 November 1950, FW Wood wrote to Professor Frank Stanley Cotton, Professor of Physiology, “You may have heard that recently there has been another outbreak of “flying saucer” stories including a photograph in “Life” magazine taken by a farmer in the mid-west who claims the objects actually flew. Unfortunately for the story, there were no independent witnesses, so we are still waiting for the first real evidence. None of the stories carried here, in explanation of the visions that many persons appear to have had, refer to the physiological basis that you proposed, and which you supported by having your class gaze at the sky and draw what they saw…I have endeavoured to counter some of the wilder claims made here, in discussing the matter with colleagues and others at Harvard, by describing your investigations…Of course, the Americans are by and large, as you probably know very well, of a somewhat temperamental and unstable nature and are given to expressing themselves volubly rather than intelligently on any matter that they find a little incomprehensible and therefore potentially a cause of fear. I would like to do something to calm those fears if possible and the only way to do that is to remove the question of the flying saucer from the realm of horrendous speculation and reason it with a grain or two of common scientific cause. I hope you have one or two to offer”.

Professor Cotton was also contacted by the Australian Military Forces (Southern Command) on 19 March 1951 with a report on “flying saucer” sightings, “As you say, since the phenomenon occurred twice, there should be further repetitions, but quite frankly I never expected to see a “flying-saucer” again, much less in company: this did not of course prevent me from keeping my eyes open. Four individuals have now witnessed this “flying-saucer” phenomenon in this area to my knowledge. Naturally the observations have been discussed in the Mess but by and large they have been treated with some incredulity – apparently: it’s more comfortable to turn the mind away from the inexplicable”.

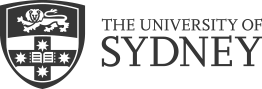

A paper by Professor Cotton argued that, “A careful analysis of the great number and variety of reports of flying saucers will indicate that at least six separate phenomena could have been involved in these and allied manifestations. Three of these may arise from something purely external to the body and three may be considered with well recognised physiological behaviour, in that their origin is within the body itself…two arise within the eye itself and one within the brain. The commoner of the optical phenomena are called ‘muscae volitantes’ and are described in the standard medical dictionary as ‘floating specks in the field of vision due to opacities in the media of the eye’. These may give rise to many queer optical effects, as of objects seen in the distance. The second are not given a name but appear as rapidly moving tiny specks which when projected against a suitable background can be seen as bright oval objects…Normally one learns to disregard them and they may only be realised under special conditions. There is little doubt that these were originally responsible for the epidemic of flying saucers reporting by hundreds of people looking for them all over the world…The visual manifestations arising within the mind embrace the great variety of ‘visions’ primarily regarded as of psychological origin. History is full of them”. This drawing is one from a set of drawings and notes from an experiment conducted by Professor Cotton, referred to in the letter by Wood, “Late in June 1947 the first reports appeared in the overseas cables following in a few days by further reports in U.S.A. and then in quick succession by reports from all over the world…when the Sydney Morning Herald published a cable “U.S. Planes ready to pursue flying saucers” I got together some twenty odd students (with no knowledge of the physiology of the eye) and I asked them simply to look at the blue sky and draw whatever they seemed to see, while looking fixedly into space without allowing the gaze to waver about or stray at all…When the sketches were handed in it was seen that some eight different features were drawn…All seven points would be characteristic of the appearance produced by the red corpuscles on the retina. Hence we conclude that the cascade of reports coming from U.S.A., Canada, South America, South Africa, England and Denmark had the same origin as in the students eyes…No one eye is free from such defects…When normal vision is upset…these strange appearances seem very real and give rise to the idea of seeing pink elephants fiery wriggling snakes [sic] etc. Possibly many of the reported visions of history have been due to some such set of circumstances”.

Not everyone was convinced with Professor Cotton’s line of reasoning, as E McDermott adamantly stated, on 10 July 1947, that they did not, “…agree with your report…that “flying saucers” are an optical illusion but think when the objects reach that stage a person’s energy is at a very low ebb”.

Flying Saucers (1947 to 1955), [REF-00080115]. University of Sydney Archives, accessed 01/05/2024, https://archives-search.sydney.edu.au/nodes/view/130540.

2 May 2024

Song for the Andersonians

This recording of Professor John Anderson, Challis Professor of Philosophy from 1927 to 1958, singing ‘Those Sydney Blues’ was made by Professor Peter Platt, who twenty years later became Professor of Music at the University.

There was second recording made of the same song in 1961, which acknowledges this 1955 recording. Graham Pont, in Don Laycock: Collector and Creator of Dirty Songs, writes, “In 1961, the late Professor John Anderson of Sydney University visited Canberra with his wife and stayed for several days at University House. Being a former student of his, I had some social contact with the old couple; but, as in my student days, Anderson was by then less convivial and more remote than he had been in his legendary past, which was coextensive with the Golden Age of Sydney University. One evening after dinner, I was practicing the recorder in my room when Anderson came knocking at the door – drawn there by the orphic tones of a Vivaldi concerto. On this occasion, the philosopher was in a convivial mood; and somehow Laycock turned up too. After a couple of drinks, Laycock suggested that he might record some of Anderson’s songs – we had heard about them many times but never been present at a performance. Anderson was a bit hesitant at first; but he finally agreed to sing three of his songs: ‘Joking Jesus’, ‘Sydney Blues’ and ‘Philosophical Blues’ (the last two being his own compositions). Laycock recorded these three on his beautiful ‘Bayer’ machine and then asked Anderson to sing some more…The songman won; and, like so many informants in the field, he refused to divulge any more to the intruding anthropologist…But Laycock did manage to record those three precious songs – wonderful memories of old Sydney University…Laycock’s title, as announced on the tape, is ‘Song for the Andersonians’. To my knowledge, there is only one other recording of Anderson’s singing – a single song in the possession of Peter Platt, the retiring Professor of Music at Sydney University”…’Sydney Blues’ is the lament of the homesick Andersonian in exile at Oxford. Anderson himself was an exile, in Australia”.

The Challis Professor of Philosophy in 1975, Professor DM Armstrong, wrote a piece in Record, the University Archives’ journal, providing some background to the song, “The University of Sydney Archives is building up a collection of the papers and other memorabilia of the great Scots-Australian educator and philosopher, John Anderson…It is not intended that the collection should be confined to Anderson’s academic work, but that it should also reflect other interests of this. Anderson liked jazz and blues, and he used to compose blues himself…As a literary composition it [the piece, ‘Those Sydney Blues’] is perhaps not one of his best blues, but it is certainly the most famous…Anderson had no love for the school of Linguistic Philosophy, then flourishing in Oxford, led by such men as Professor Gilbert Ryle, John Austin and P.F. Strawson, and had no doubt of his own philosophical superiority. The blues was written for Peter Gibbons, a student of Anderson’s, at that time a post-graduate student at Magdalen, now Senior Lecturer in Philosophy at the University of N.S.W…Doug McCallum, now Professor of Political Science at the same university, was another Andersonian student at Oxford at the same time. The Lincoln was a famous coffee shop in the late forties and fifties, conveniently situated in Rowe Street, just opposite the Long Bar of the Australia Hotel. The Tom Tower of Christ Church is, of course, one of Oxford’s most famous erections. The Trocadero, a dance-hall in George Street, near the Town Hall, now pulled down, had a rather strange edifice on its roof”.

Professor John Anderson Singing “Those Sydney Blues” (1955), [REF-00088311]. University of Sydney Archives, accessed 02/05/2024, https://archives-search.sydney.edu.au/nodes/view/141061.

3 May 2024

The Nature of Historical Records

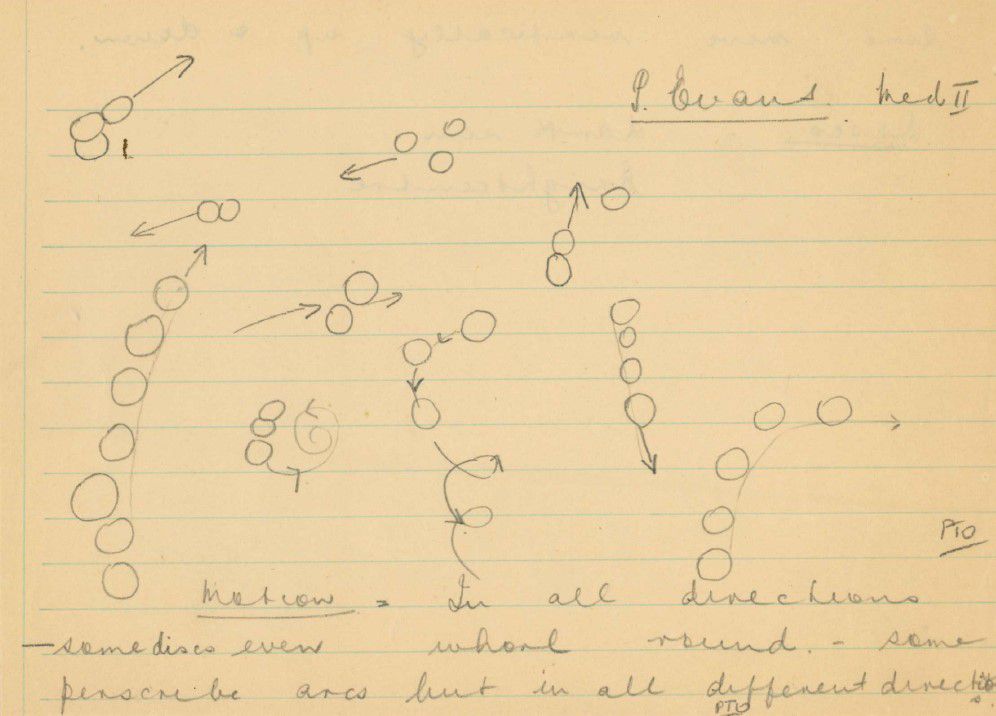

In 1953, the University invited local and international applications for the newly established role of University Archivist. David Neil Stirling Macmillan, it was noted was, “…drawn first to the post because it was an appointment of an archivist and such appointments are not very thick on the ground”, but Macmillan of Girvan, Ayrshire, Scotland, was fortunate enough to be granted his wish. On this day, seventy years ago, on 3 May 1954, the Vice-Chancellor reported to Senate that, “He wished to make a recommendation concerning the appointment of a University Archivist. He informed the Senate that 33 applications had been received after advertisement, and that he had appointed a small Committee consisting of Professor E. Ford, Mr. H. D. Black and the Registrar to assist him in considering the applications. The Committee have selected the two most promising overseas candidates, Miss Jean Imray and Mr. D. S. MacMillan, and the Vice-Chancellor had asked the Registrar of the University of Glasgow, Dr. R. T. Hutcheson, to interview the two candidates and report on their qualifications and suitability for appointment….In his opinion both were well qualified candidates but Mr. MacMillan seemed to be personally more suitable for appointment. The Committee had interviewed one local applicant with archives training but had decided that he was not qualified or suitable for appointment. Mr. MacMillan is 28 years old and graduated from the University of Glasgow in 1949 with the degree of Master of Arts with Second Class Honours in History. He has had archives experience in the Scottish Records Office, Edinburgh, and his duties there included assistance to scholars and research students and lecturing to classes of University students on the nature of historical records and their relevant to the various branches of historical study. He has also been employed by the National Register of Archives Committee, Scotland. Mr. MacMillan served for three years with the Royal Navy. The Vice-Chancellor moved that Mr. D. S. MacMillan be appointed to the position of University Archivist. The motion was seconded by Mr. Black, put to the meeting and carried”.

Macmillan was informed of this decision on 11 May 1954 and advised that, “The salary range for this position is £1,100-$1,450 (Australian) per annum…and your commencing salary has been fixed…at £1,1000 (Australian) per annum with annual increments of £50 to the maximum of the range…Provided you are proceeding direct to Sydney to assume office, your salary will commence from the date of embarkation at the overseas port. Assuming you are single, an amount of up to £150 (Sterling) has been allowed to cover the cost of your fare to Sydney. In addition, the Finance Committee will consider a claim for removal expenses of up to £175 (Australian) on your arrival in Sydney”. On 19 May 1954, noting that, “The terms and allowances, etc. are very generous”, Macmillan noted that, “I am very happy with this outcome, and my wife is very pleased also”. In a separate letter, written on the same day, Macmillan formally accepted the employment offer and admitted that, “Since the date of my application I have married, and am uncertain as to the position re fares, but am prepared to pay my wife’s fare”. The University, however, made available an additional £150 (Sterling) to cover the cost of Macmillan’s wife traveling with him to Sydney. The couple travelled on the Orontes from London to Sydney on 11 August 1954 and arrived on 16 September 1954. The University initially arranged for a one-year lease for a furnished apartment in Dulwich Hill for, “…£6/11/- per week, which by standards in Sydney at the moment is very reasonable”, however, on 9 September 1954, an internal memorandum noted that, “Mr. and Mrs. Macmillan have been booked in at the guest house at…McMahon’s Point, for 16th and 17th September. On Saturday, 18th September, they will be able to move into a cottage at…Croydon”.

The Gazette announced the news in October 1954, and Macmillan appears to have hit the ground running as included in the same edition of the Gazette was a brief “Appeal for Old Records” by him, “The University will be most grateful for gifts of old documents and correspondence dating from before 1900 and relating to the University, to families connected with the University and to the commercial and economic development of Australia generally. An appeal is made to all graduates having material of this kind in their possession, or knowing of its survival in the hands of others, to inform the University Archivist of its existence. Such material may either be presented outright or placed on loan to the University, where it will be properly looked after and made available for historical research. So much of this valuable raw material of history has been destroyed or lost that it is essential that what remains should be adequately preserved”.

In October 1958, Macmillan provided an update in the Gazette, noting that, “The University of Sydney took the lead among Australian institutions in 1954 when the decision to organise the records of the University was made. In the last four years a great mass of material – thousands of feet of administrative and departmental records – has been surveyed and listed. In 1958 the greater part of this accumulation has been brought together in the new records repository, which has been specially equipped for the purpose…Archives work has been a long-neglected field in Australia…The University of Sydney has played its part in the movement for archives reform”. This report was followed by the Guide to the Records of the University of Sydney, written in 1962, covering the period from 1849 to 1960. In May 1968, Macmillan, again writing in the Gazette, reminisced about the “First Fourteen Years”, “Perhaps the most outstanding, however, was not that of a document, but of a collection of nearly two hundred small glass plates – these are extremely early photographic negatives made using the collodion or wet-plate process by Professor John Smith, the University’s first Professor of “Chemistry and Experimental Philosophy”…As far as we have been able to discover, the University of Sydney is the only university built in the 1850s which has a photographic record of its construction. (The John Smith collection is still held by the University Archives.). Macmillan notes that, “Over the last thirteen years several thousands of scholars and researchers have made use of the university archives, and thousands of enquiries about the history of the University have been answered”.

David Stirling Neil Macmillan, University Archivist (1954), [REF-00046275]. University of Sydney Archives, accessed 03/05/2024, https://archives-search.sydney.edu.au/nodes/view/80736.

Explore the blog for other posts from the University of Sydney Archives and follow us on Instagram.