The University Archives turns 70 on 3 May this year. To celebrate this milestone, check the blog at the end of each week for the week’s special stories from our collections.

18 March 2024

Why Did the Student Cross the Road?

On 20 March 1961, a memorandum “Re Crossing of City Road” noted that, “Mr Maze has raised the problem of crossing City Road, as the traffic crossing City Road near the entrance gates is already heavy and must increase commensurate with the number of departments we place in Darlington…Now what I have in mind is this, that some time during this year we may endeavour to place a foot bridge over City Road from the area south of the Carslaw Building, spilling out on to the area now occupied by 178 and 180 City Road, with access into Alma Street but if this is not possible with access into Codrington Street, such access to be obtained by the demolition of 178 and 180 City Road, and No. 1 Codrington Street. The thing that I do not know is where this is an ideal position, and if it is not an ideal position, where it could be made to work without adversely affecting your plans for the development of the area east of the Carslaw Building between the Carslaw Building and City Road. I think it is fairly safe to assume that an underpass across City Road is something like 20 years in the future”.

On 30 June 1964, the Building and Grounds Committee discussed the matter and declared that, “…the building of a bridge should be proceeded with as a matter of urgency” as they had, “…received complaints regarding students who has been involved in car accidents at this site”. This issue was brought up again by the President of the Students Representative Council (SRC) on 8 July 1964, “…a female student in the Faculty of Arts, was struck by a motor vehicle whilst in the pedestrian crossing and as a result of the accident suffered a fractured skull, which will prevent her pursuing her academic work…I confirm the advice of the Vice-Chancellor that the erection of a bridge would be pursued with all due haste”.

On 7 June 1965, the Vice-Chancellor reported to Senate that construction of the footbridge was underway and a Certificate of Practical Completion was presented to the University on 15 March 1966. On 26 May 1966, the Buildings and Grounds Committee approved the naming of the footbridge as the Keith Murray Footbridge, after Keith Anderson Hope, Lord Murray of Newhaven. Murray was Chairman of the Committee on Australian Universities in 1957, and with the Murray Report, was instrumental in the University’s move into the Darlington area.

City Road Showing Students Crossing Before Construction of Keith Murray Footbridge (1964), [REF-00051455]. University of Sydney Archives, accessed 18/03/2024, https://archives-search.sydney.edu.au/nodes/view/79755.

19 March 2024

A Sticky Wicket

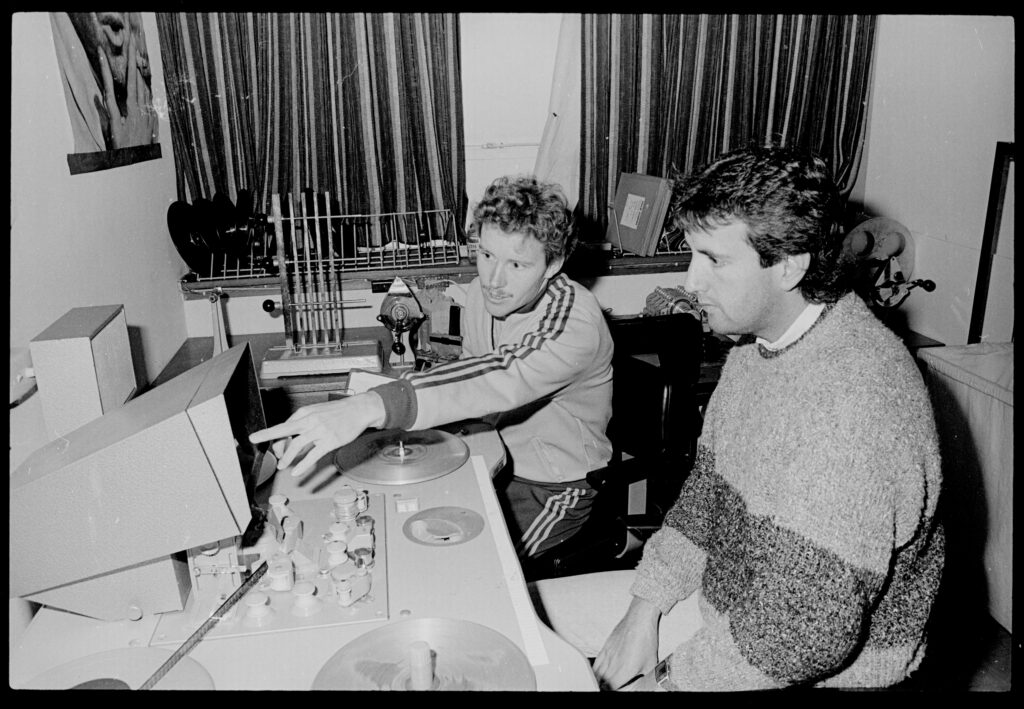

David Patterson, a Bachelor of Education honours student, created a test in 1986 to examine differences in motor behaviour amongst cricketers, to determine how reaction and reflex times impact their batting. Patterson, who played cricket for the Manly-Warringah Club himself, hypothesised that, “…top class batsmen will show better reaction and movement responses to the tests than less skilled batsmen”.

Forty cricketers, including twenty from the New South Wales cricket team, were, “…shown films of a bowler making a variety of deliveries. The cricketers have to decide where the ball is likely to land and how they would play it. The time taken to make such a decision and the accuracy of the decisions are recorded”. In a second test, the cricketers’ reaction times were recorded as they responded, “…to a flashing light by moving either a hand or a foot from one switch to another”.

The test was designed by Patterson to aid in training, allowing the participants to see, “…what areas they have a weakness so they can concentrate on that and adapt their training program accordingly…the state team bowlers, for example, could find the results particularly helpful”. It was Patterson’s goal to apply the testing, “…to other sporting games such as base-ball, squash, tennis and badminton”.

David Patterson, BEd Student, Testing Cricketer David Gilbert (1986), [REF-00012746]. University of Sydney Archives, accessed 19/03/2024, https://archives-search.sydney.edu.au/nodes/view/31205.

20 March 2024

A Pineapple Regaling Learning and Colonial Youth

University Archivist, David S Macmillan, reported in the March 1963 Gazette that, “Recently, in the old strong-room of the University, situated in the great Main Building designed and erected by Edmund Blacket, there came to light a handsome metal seal which is one of the earliest relics of the very first days of the University. For the first two years of its existence, from 1850 to 1852, the University had no buildings, no staff, and no students. In effect, it was a university in embryo only, and consisted of the Senate, made up of sixteen Fellows, who had been appointed by proclamation of the Governor, Sir Charles FitzRoy, on December 24 1850, a few weeks after he gave his assent to the Act incorporating Australia’s first university”.

On 3 March 1851, at its second meeting, Senate appointed four Committees including one, “…to propose for the consideration of the Senate a device for a Corporate Seal, and they be empowered to advertise, and offer a premium for a design of the same if necessary”. The matter was raised again 17 March 1851, however, it was determined, “That the subject of the University Seal and motto be postponed for further consideration”. On 7 April 1851, the Committee, which consisted of Charles Nicholson, Francis Merewether and Bishop Charles Henry Davis, “…reported progress and asked leave to sit again which was granted”. On 10 April 1851, Senate heard that, “The Committee appointed to consider the subject of a corporate seal beg to lay a number of devices on the table for the selection of the Senate”. It was determined by William Charles Wentworth and Justice Therry, “That the female figure of Australia rising from the sea with the motto “Sic itur as astra” be adopted”, however, Stuart Donaldson and Nicholson voted, “That the design prepared by Mr Claxton [Marshall Claxton] be adopted”. Ultimately, the Claxton design, “…with certain alterations”, was accepted, “…with the motto Virtutem doctrina paret”. A supplementary Committee, with Nicholson, Davis, and Donaldson, was then established to have the seal engraved.

Macmillan describes the winning design in the Gazette, “…a seated female figure, probably denoting the Spirit of Learning, held out a wreath of laurel over a kneeling figure, obviously intended to represent the youth of the colony. To give some local flavour to the design, Claxton had incorporated a diminutive Southern Cross in the heavens, and, not a kangaroo, emu or lyre bird, but a “blackboy” plant, or Anthoria Australis, which appeared rather incongruously in such a manner as to suggest that a pineapple lay ready to regale both Learning and Colonial Youth after the completion of the ceremony…In its rather naïve but charming portrayal of the allegorical figures, and its symbols of the new land, so incongruously juxtaposed with them, it typifies the spirit of the time and the uncertainty of the men who wanted to design a traditional university in a new land”. The seal was ready by January 1852 and was occasionally used for other purposes than as a seal, such as being printed on the title pages of the early University Calendars.

Original Common Seal of the University (No Date), [REF-00077067]. University of Sydney Archives, accessed 20/03/2024, https://archives-search.sydney.edu.au/nodes/view/127253.

21 March 2024

The Special Needs of the University

The façade of the Madsen Building still reveals its original occupant – the National Standards Laboratory, part of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (now the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO)). The building was designed and constructed by the Department of the Interior Works between 1939 and 1944 and represented the conjoint efforts of the University and the Government to collaboratively conduct research on matters of national importance.

The relationship between the institutions, however, was not always amicable. On 20 July 1951, JL Pawsey of the CSIRO wrote to the University and noted that, “It has been found desirable to erect an elevated apron…I hope that you will have no objection to the erection of this structure”. It appears, however, that the CSIRO did not wait for the University’s approval as ten days later on 30 July 1951, the University wrote back that, “In view of the circumstances, the University will not require removal of the apron, but would appreciate being consulted before any other extensions or alterations are made to the temporary buildings associated with the Radiophysics building. At the same time I am directed to remind you that the University proposes to enforce the condition under which permission was granted for the erection of temporary structures, namely that they would be removed within one year from the formal cessation of hostilities”.

The Buildings and Grounds Committee proposed to Senate on 4 November 1963 that, “The Committee recommends that representations be made to the Prime Minister, the C.S.I.R.O. and to the Australian Universities Commission requesting that the National Standards Laboratory be handed over to the University for its own use. Professor Harry Messel of the School of Physics was consulted on 8 November 1963 and asked, “…if you could assist me in preparing the case we should present for the acquisition of the National Standards Laboratory. I feel that it should be a specific one rather than just a general request, and that it would be better for the University to indicate that it has specific uses in mind”. It was noted, however, that similar letters were also sent to Professors WN Christiansen and Thomas Gerald Room and Dr Mills.

Professor Messel’s reply, dated 12 November 1963, was emphatic, “I would like to say right from the outset that the School of Physics is exceedingly interested in the space…You may recall that over the past few years I have mentioned to you personally on several occasions the hope that this space, or portion of it, might be allocated to Physics. As you are aware the School of Physics is exceedingly crowded and the small additional wing going up at the back of the School at present, will fall short of our space requirements, especially in regard to the research work of the five departments in the School…you might very well wish to allocate a portion of the space which becomes available to another group, such as Electrical Engineering. There is considerable merit in housing some of the research effort of departments whose work is closely associated”. Professor Christiansen affirmed this sentiment on 15 November 1963, “…the University should put the present CSIRO buildings to use in a manner which conforms most closely to the purposes for which the buildings were designed and equipped. This purpose was, of course, research work in the fields of Electrical Engineering and Physics…This would bring together the post-graduate research in similar fields in the Schools of Physics and Electrical Engineering to the benefit of all”.

On 14 April 1964, the University wrote to the CSIRO and noted that, “The preparation of the submissions for the Capital Works Programme required much detailed planning…Our submission however will depend greatly on the availability or otherwise during the triennium of the building occupied by the National Standards Laboratory…When the National Standards Laboratory was first established on this site, it was located in an area of the University which was far removed from the geographic centre of the University. Our building programme since 1958 and our expansion into the Special Uses Area beyond City Road has changed the geographic centre of the University, which now is clearly located somewhere in the vicinity of the City Road gates. I think it is quite clear that the building should be used for University purposes as quickly as possible”. The CSIRO responded to the University’s request on 3 June 1964, “We have in hand a considerable number of major building projects to which we must give greater priority than the National Standards Laboratory…which will occupy our programme at least until 1969. However, the Executive is anxious to move the National Standards Laboratory to a new site and the situation would be different if special finance could be made available because of the special needs of the University”.

The matter of officially acquiring the building stalled for over a decade until a letter from the CSIRO, dated 26 April 1977, noted, “I would appreciate a copy of the prepared schedule for record purposes. The schedule will be the common reference in respect of the handover of the building after the move to Bradfield Park”. The space, meanwhile, was fought over by various departments, faculties, and schools.

Madsen Building – Occupied by CSIRO (1940s), [REF-00048938]. University of Sydney Archives, accessed 21/03/2024, https://archives-search.sydney.edu.au/nodes/view/80215.

22 March 2024

Handle with Care

On 7 September 1956, a memorandum to the “Heads of Departments” was circulated as, “The Public Health Advisory Committee…is seeking information as to the value and feasibility of extending the labelling of chemicals in accordance with the requirements of State Poisons Legislation to all laboratories. It is thought that suitable regulations widening the labelling requirements of chemicals might encourage safety measures in laboratories”. The draft version of this memorandum noted that it was intended for “science-type Departments only”.

Professor Neville Collis-George, Professor of Soil Science, considered it, “…advantageous if there a labelling code (colour or number) which gave minimum toxic quantity in one dose and cumulative or long term toxic quantities. This would not inconvenience our use of poisons”. While other professors also supported the idea of consistent, uniform labelling, Professor of Biochemistry, Jack Leslie (JL) Still, argued on 14 September 1956 that, “The labelling of reagent bottles in our laboratories is of a very temporary nature; for example, many bottles of reagent containing poison may be prepared for a class or experiment lasting only one day. The purchase of extra labels and the fixing and removal of them would involve the department in extra money and time. All our staff members are competent to handle poisons and it is part of student training that this knowledge is imparted…The labelling of poisonous and hazardous materials by the manufacturers has undergone a great change in the last few years and now leaves little to be desired. It seems to me there would be little value in the proposal and it would undoubtedly add to the cost of research, and more especially of teaching”.

Safe Management of Potentially Explosive Chemicals (No Date), [REF-00082595]. University of Sydney Archives, accessed 22/03/2024, https://archives-search.sydney.edu.au/nodes/view/133155.

Explore the blog for other posts from the University of Sydney Archives and follow us on Instagram.